When Ozzie Albies signed his current contract, I decried it in such terms that, well, “decried” was an accurate description. This 22-year-old middle infielder, coming off a season of 24 home runs and 4.0 WAR, had signed away his prime earning years to the Braves for seven years at an average of $5 million per. Two option years could keep him in Atlanta through 2027 without increasing the contract’s AAV. It was an all-time swindle, I wrote. Esau got a better deal when he sold his inheritance for a bowl of stew.

Six years later, I sit here contemplating a question that once would’ve seemed unfathomable: Should the Braves pick up those option years?

Through his first 83 games, Albies is hitting .223/.297/.321, which is a wRC+ of 74. He has never before hit under .259, nor slugged under .450, nor posted a wRC+ under 100 in any previous healthy season. There’s probably a little bad batted ball luck in there, and some malaise from Atlanta’s comprehensively frustrating, injury-riddled season to date.

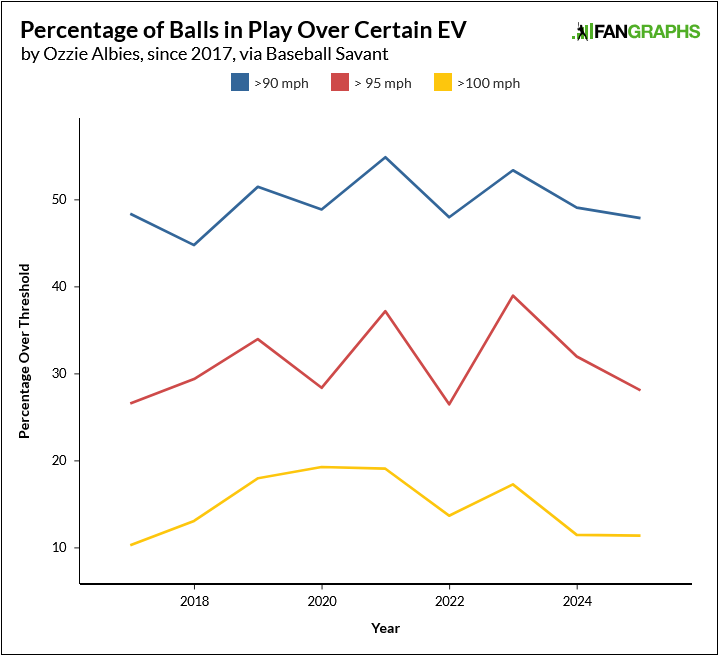

But Albies is only underperforming his xwOBA by nine points, and his hard-hit rate, 28.1%, is in the seventh percentile among major league hitters. For a player who’s profited so immensely from the right combination of contact quality and launch angle, here’s a troubling number: His barrel rate is just 3.4%, a 10th-percentile figure relative to the league and Albies’ lowest figure in that category since his rookie year. In 2023, when he hit 33 home runs, Albies ran a barrel rate of 8.2%. In 2021, his other 30-homer season, Albies’ barrel rate was a career-high 9.3%.

Denuded of his potent bat, Albies is just barely keeping his head above replacement level. But as to the question I posed above the break — might the Braves cut him loose after this season? — that’s one of those deliberately inflammatory rhetorical questions people like me let loose in order to get you to read.

As poorly as Albies has hit this year, it would be the shock of a lifetime if Atlanta didn’t pick up his option, even if he gets to September and his wRC+ is still in the Ford administration. There are two reasons.

First, it’d take a pretty ruthless bastard to fire Albies after all he’s done for the Braves. Part of the reason I was so outraged on Albies’ behalf when he signed this extension had to do with his immense potential. This tiny little man had already played more than 200 games in the majors before he turned 22, and not only survived but performed. It was not unreasonable then to expect Albies to turn into something like a switch-hitting Mookie Betts.

That didn’t happen, of course, but over the first six seasons of that extension, he played 656 games with a 110 wRC+, and even with the pandemic and various injuries, he produced 15.0 WAR over that time. But numbers don’t really do justice to a franchise stalwart. He’s made three All-Star teams, won a World Series, sold God knows how many jerseys and t-shits. Not to generalize off one data point, but my mother-in-law is a huge Braves fan, and Albies is her favorite player.

This isn’t some itinerant middle reliever; this is a lifer. There probably are front offices out there ruthless enough to ditch Albies after one really bad season, but Alex Anthopoulos and the Braves keep getting players to sign long-term under-market extensions because it’s supposedly a good place to play.

Second, like everything else about Albies’ contract, his first option year is unbelievably cheap: just $7 million. Moreover, while his 2027 team option has no buyout, if the Braves wanted to cut Albies this offseason, they’d have to pay $4 million to get rid of him. In essence, that makes this a $3 million decision.

For a guy entering his age-29 season who was an All-Star and got MVP votes two years ago, $3 million is nothing. Here’s a sampling of infielders who are either way older than Albies, or way more washed than Albies, or both, and what they got last winter on the open market from teams to which they (for the most part) had little or no emotional attachment:

Ozzie Albies’ Free Agent Comparables Unless He Snaps Out of It

Albies is just flat-out worth $3 million next year. If he’s this bad again in 2026, then we can talk about his 2027 option, but that’s another blog post for another day.

Having established that the answer to a question nobody was asking is, “No,” let’s get to the scary part.

Albies was never a massive bat speed guy. It’s not his fault; he’s little. This might seem a bit weird to say, because it feels like a million years ago and he’s still only 28, but Albies was one of the first players who developed as a prospect post-swing plane revolution. Players who had good hit tools were taught to swing harder and put the ball in the air, and Albies was great at it.

Even now, he’s in the top quartile of the league in ideal attack angle percentage. He’s 18th in air-pull rate among 281 batters with at least 100 balls in play this season.

But he’s not hitting the ball as hard as he used to:

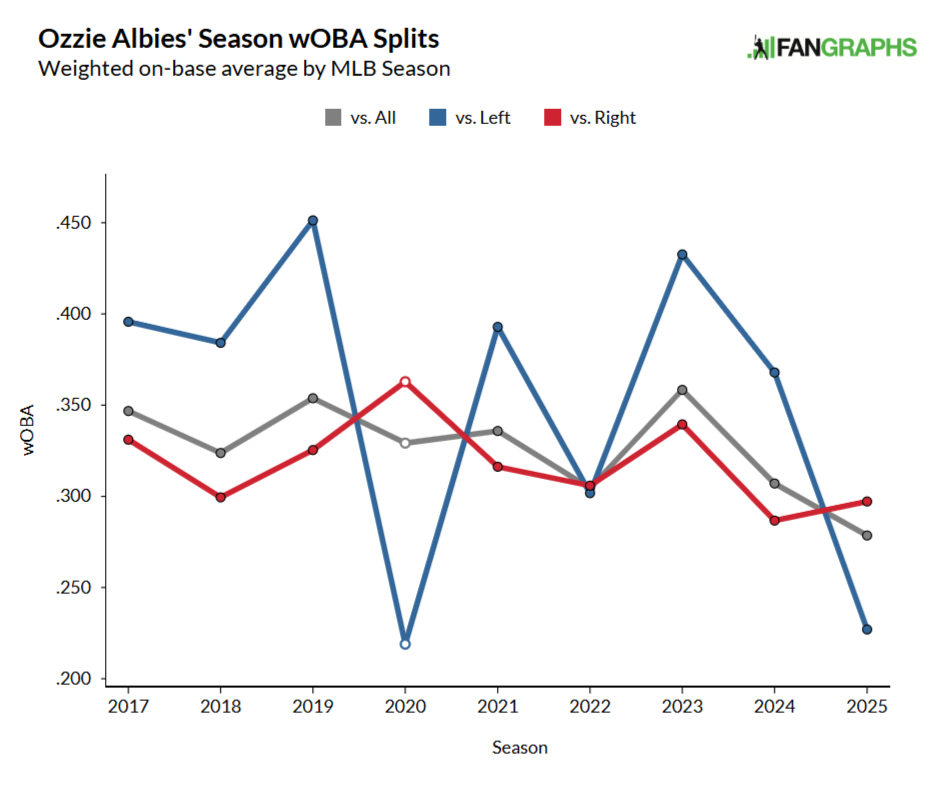

The thing that makes Albies tricky to evaluate is that he, more than almost any other hitter, is actually two hitters. He’s a switch-hitter with two extremely different swings. I actually asked him about this a couple years ago when I was kicking around an article on the decline of the switch-hitter. (The Athletic published a similar article while I was it kicking around, so I never used the quotes.)

Albies learned how to switch-hit in the minors; he’s naturally right-handed (obviously, given where he plays), but when you try to mirror your natural swing, he said, there were always differences. And he’s toyed with different stances and swing types over the years; he’s extremely open from both sides, but that quality has gotten more extreme with his left-handed swing and less extreme with his right-handed swing. Here’s what he’s been doing in 2025. First, from the left side:

And then from the right:

The tweaks he made — he started going slightly less extremely open in 2024 — have actually helped Albies put better swings on the ball. Even as Albies’ bat speed has suffered quite a bit from the left side, his losses have been minimal from the right, where he’s squared the ball up much more frequently over the past two seasons:

Ozzie Albies’ Bat Speed

| Year | Batting | Avg. Bat Speed (mph) | Fast Swing Rate | Squared Up/Contact% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | L | 70.1 | 10.7 | 30.8 |

| 2024 | L | 68.9 | 6.5 | 30.2 |

| 2025 | L | 68.3 | 4.5 | 30.8 |

| 2023 | R | 69.9 | 11.7 | 30.1 |

| 2024 | R | 69.4 | 10.0 | 39.8 |

| 2025 | R | 69.4 | 12.7 | 40.9 |

SOURCE: Baseball Savant

Albies’ performance as a switch-hitter is one of my greatest baseball fixations. I’ve come to realize that many of my fixations come from traumatic arguments I had about the early 2010s Phillies as a young blogger, and this is no different. Back then, Shane Victorino was a switch-hitter with two distinct swings, just as Albies is now. From the left side, Victorino had a slappy swing; from the right side, he looked like Albert Pujols, and with not-much-worse results. Victorino had a career wRC+ of 93 batting left-handed, and a career wRC+ of 130 batting right-handed.

This is relevant to Albies because he is (or at least has been) a monster against lefties hitting right-handed: .326/.351/.537, a wRC+ of 135. Against right-handed pitching batting left-handed, he’s OK at best: .245/.309/.428, for a 95 wRC+.

The problem for Albies now, as it was for Victorino then, is that way more pitchers throw right-handed than left-handed. For his career, Albies has seen almost three right-handed pitchers for every lefty. For every plate appearance he takes as Manny Machado, he takes 2.8 as Ceddanne Rafaela.

Victorino eventually gave up switch-hitting at the end of his career, and I put that example to Albies when we spoke, as gently as I could: Would he ever consider hitting right-handed exclusively?

“We’ve talked about it before, but it’s not a thing I think I would do.”

Why not?

“Because I’m a switch-hitter,” he said, with a weighty silence afterward to indicate that he’d prefer to drop the subject.

Nevertheless, Albies tried going right-on-right at the end of last season. He’d broken his left wrist in July, and was racing to get back on the field in time to help the Braves make the playoffs. It wasn’t a big sample — nine games, 33 PA — but neither was it a rousing success. He hit .226/.273/.452.

This slump, which is quickly turning into a bad season, full stop, would ordinarily be a perfect opportunity to try something new. To reinvent oneself, even. But Albies can no longer count on crushing left-handed pitching.

He’s maintaining his bat speed, he’s hitting the ball in the right places, and the power is just gone:

In 90 plate appearances from the right side this season, Albies has just three walks and four extra-base hits, all doubles, leading to a wRC+ of 39. For the first time in his career (pandemic season notwithstanding; he only played 29 games that year), Albies is doing significantly worse against left-handed pitching.

What I don’t know is where the bleeding is coming from or how to stop it. Albies is chasing more from the right side than in any season except 2022, but he ran a 43.0% chase rate in 2023, when he hit .391 as a righty and set a career high in home runs. He’s on pace to set a new career high in walk rate, but if there are glaring signs of overall passivity, I don’t see them. His SEAGER is below his career average, but he was never among the league leaders, and it’s not much lower than it was in 2023 anyway.

Albies’ decline is mysterious enough to tempt one to look for outside explanations: changes to the baseball, maybe, or lingering effects from that broken wrist. Albies wouldn’t be the first star player — or even the first extremely short second baseman of his generation — to get suddenly and inexplicably lost for a season. Jose Altuve was dreadful in 2020, his age-30 season, then popped back and made the All-Star team in 2021. He finished fifth in MVP voting in 2022. Only now, in his age-35 season and amid a position change (in my opinion, an ill-advised one) is he well and truly slowing down.

If Albies is in line for a similar bounce back, picking up that $7 million option will be the smartest decision Anthopoulos ever made. But one of the most reliable skills in baseball has evaporated, practically overnight, and I’m starting to worry.