Floyd Steadman was separated from his mother aged one, lived homeless in London as a 10-year-old to escape his father’s beatings, and grew up as a child in care, unknowingly living next door to a serial killer, before going on to make a success of himself, as a rugby player and teacher, who was – and still is – an inspiration to many, including Lions captain-in-waiting Maro Itoje.

No one will be happier for Maro Itoje than fellow Saracens legend Steadman if Andy Farrell ends up choosing him as the man to lead the Lions in Australia this summer, which looks extremely likely now that Caelan Doris, the other main contender, needs shoulder surgery.

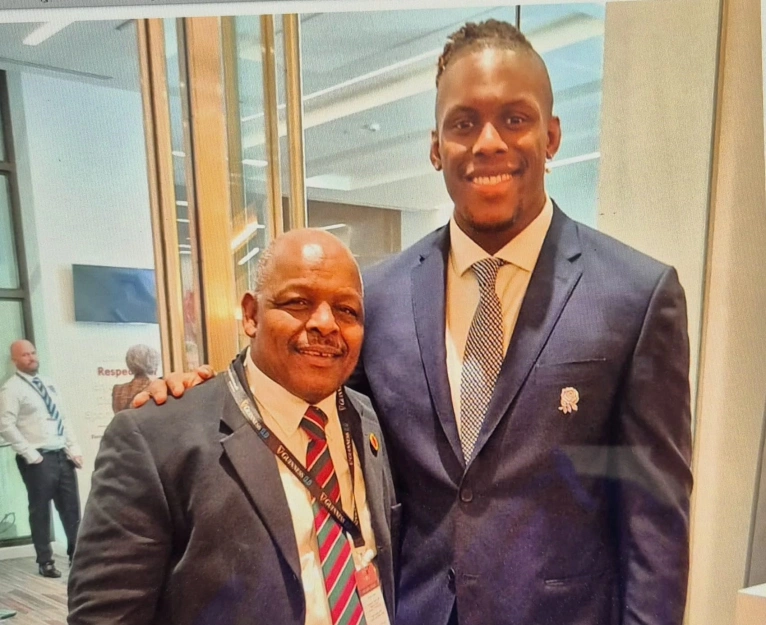

Steadman, the first black player to captain a leading English club in the 1980s when he was appointed Saracens skipper, is the man Itoje credits with getting him into rugby, and the two have remained close ever since, even if their backgrounds couldn’t have been any different.

Steadman, or Mr Steadman, as Itoje still calls him, was the England and Lions lock’s headmaster at Salcombe prep school in north London, and the first person to recognise how well suited he would be to the sport.

“Even at the age of 10, he was bigger than me, and was exceptional in everything he did. One day I told him: ‘You would be a really good rugby player, you’re ideal for rugby.’ He was a bit reluctant, but I said: ‘I’ll speak to your Dad about it’ and I did. I said: ‘You’ve got to get him playing rugby and you’ve got to take him to Saracens,’” he said.

“The rest, as they say, is history. It’s lovely to hear him say in subsequent interviews how that conversation helped to influence him to play rugby. Hopefully, he’ll be the next captain of the Lions.”

Speaking to The Guardian four years ago, Itoje told the story himself. “I paid little attention to rugby until Mr Steadman suggested I play, but I followed his advice. I began playing when I attended St George’s School and then went with a classmate to Harpenden Rugby Club.

“Mr Steadman rarely mentioned that he had played for Saracens at such a high level. But his love of rugby and Saracens always came through when he spoke about me playing, and it is good to see him when he comes and watches us play.”

Discovering Itoje is but a small part of an incredible life lived by Steadman, the details of which are laid out in full in his autobiography, ‘A Week One Summer’.

The title of the book derives from the time he spent living homeless in the suburbs of north London as a frightened 10-year-old fed up with being physically abused and berated by his father, although one week turned into three as he found refuse in a neighbour’s shed and then a local adventure playground, paying for food with the money he earnt on an early morning milk round.

Steadman and his sister had already spent time in care after his mother left home when he was only one, to escape a toxic marriage and the violence that came with it. And he found himself back in the hands of the local social services when his father refused to take him back in after he’d had enough of sleeping rough.

Well looked after by his foster parents, Uncle Bill and Aunt Betty, Steadman grew up in Cricklewood, 30 yards away, it turns out, from the home of serial killer Dennis Nilsen. Thankfully, Steadman and his fellow dormers were wise enough to have a second sense about their near-neighbour and never asked for their ball back whenever it went over the adjoining wall.

At Kingsbury High School, his PE teacher, Brian Jones, a Welshman, pushed him towards rugby. “I think it took me about half of a game’s lesson to fall in love with the sport. I was small for my age but had broad shoulders – physically and metaphorically – and I loved tackling,” he recalled.

Steadman also enjoyed the notoriety he was beginning to attract for his prowess in the sport, which led to county age-grade appearances and the school first XV captaincy.

From there, he joined Borough Road College (now part of Brunel University), which was famed for its excellence in sport, but only after he’d had to beg his father several times to sign the papers needed to get him a grant.

On leaving Borough Road, Steadman had his pick of London clubs. Harlequins and Wasps, where he’d played for the schoolboys’ team, were a cut above Saracens at the time, but he chose them, mainly because he knew he’d stand a better chance of a game.

Steadman ended up playing 469 games for the men in black, a figure Itoje could only dream of, even with his incredible levels of durability.

“I had opportunities to leave – Jack Rowell once asked me to join Bath right in front of our coach, Tony Russ – but I chose to stay. Either the time was right, or it was through a sense of loyalty,” said Steadman.

Steadman’s loyalty to Saracens stemmed from being made club captain at the age of 23. As the son of Jamaican immigrants, who came from a broken home, Steadman was the polar opposite of your stereotypical rugby union captain.

Racism was rife in society – Steadman and his fellow black players often had to put up with racist chants and comments – so he was eternally grateful to those on the club committee who chose to put their necks on the line and saw past the colour of his skin.

Steadman led Saracens to promotion from the old Second Division and into what is now known as the Premiership. And, in that first season up, in 1989/90, Saracens defied the odds to not only stay up but also challenge for the title, with a defeat to Wasps on the last day scuppering their hopes of finishing top.

That season proved to be Steadman’s last as a player – his knees were shot by then – and his teaching career began to really take off.

Steadman became only the second black headmaster of a private prep school when he was appointed by Salcombe, and he was head of four private prep schools in total, as he successfully overcame what he describes as the unconscious bias he faced because of the colour of his skin to climb the education ladder.

However, his contribution to life extends way beyond education and rugby, with the former scrum-half proving to be a brilliant advocate for diversity and inclusion and an ambassador for the Drive Forward Foundation, a charity that provides education and opportunities for children and young adults who have grown up in care.

In 2023, he was awarded Freeman of the City of London status, the Rose Award from the RFU for the impact he’d made in rugby, received an OBE at Buckingham Palace from Princess Anne, and returned the next day as a guest of the King and Queen for the 75th anniversary celebration of the start of the Windrush generation who came to rebuild post World War II Britain. And then, last year, he was made a Deputy Lieutenant for Cornwall.

Spotting Itoje’s potential may not have been recognised in such a grand way, but if his former protégé ends up leading the Lions to a series win in Australia, supporters of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales will be thankful for that passing conversation in the school corridor some 20 years ago.