Michael Busch had a pretty nice 2024. In his first taste of everyday playing time in the majors, he hit .248/.335/.440 and socked 21 homers on the way to a 118 wRC+. After years spent in the minors in the Dodgers system, he looked to finally be delivering on his high-strikeout, high-BABIP, high-doubles promise. The Cubs penciled him in as their everyday first baseman. That’s not an imposing batting line, but it’s better than average, so the team spent its winter trading for Kyle Tucker, not trying to upgrade from an already-acceptable situation at first base.

You’ll notice that I said high doubles instead of high power. That’s because Busch had desultory bat speed numbers; he was in the 24th percentile with a 70.3-mph average swing speed. It wasn’t an issue of him having a hard swing and a soft swing that he deployed at different times, either. His fast-swing rate, or the percentage of his swings measured at 75 mph or higher, was a mere 11.3%; league average is around 23%. Busch was adept at getting his barrel to the ball and posting good exit velocity numbers, but that’s generally a recipe for doubles instead of homers. He hit 28 doubles, two triples, and 21 home runs last season, about what was expected from his profile. He got the ball in the air a lot and still hit for a high BABIP – sounds pretty good to me.

What do you think Busch could do to improve his performance in 2025? My immediate answer: Swing faster and hit more homers. Hey, check it out! Busch has already hit 18 homers this year in just over half a season. He’s on pace to shatter his performance last season in pretty much every statistic. He’s hitting .297/.382/.562 with a 165 wRC+. There’s just one problem with my swing-hard-and-prosper theory: He’s not swinging harder.

Indeed, Busch is swinging more softly than he did last season, albeit only narrowly. His average swing speed is down to 69.7 mph, and his fast swing rate is just 8.5%. The list of players with 15 or more home runs whose average swing speed is slower than Busch’s is only two guys long: Isaac Paredes and Taylor Ward. Of course, the presence of Paredes is always suggestive. So is Busch lifting and pulling his way to success? In a word: No.

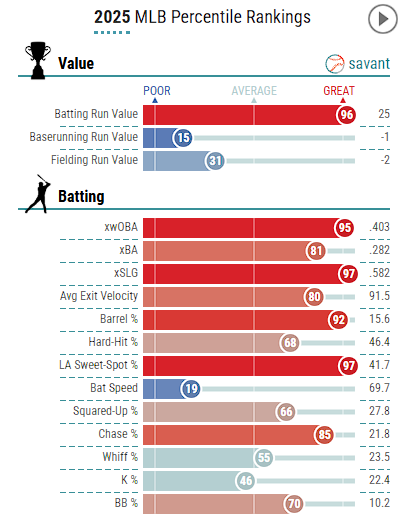

Busch is his own brand of slow swinger with pop. We’ll let Baseball Savant tell the story. Here’s how Paredes measures up by the suite of expected stats and Statcast measures of production:

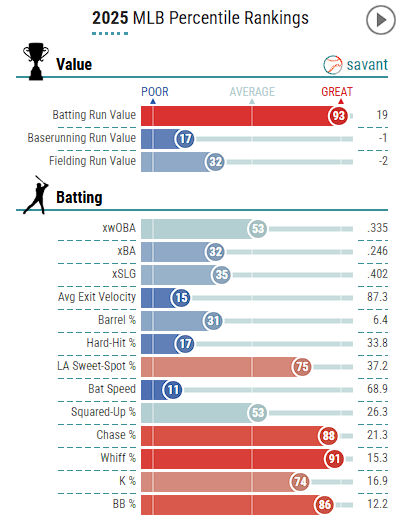

Phenomenal, cosmic actual batting run value; iiiitty bitty expected stats. Busch’s board looks nothing like that:

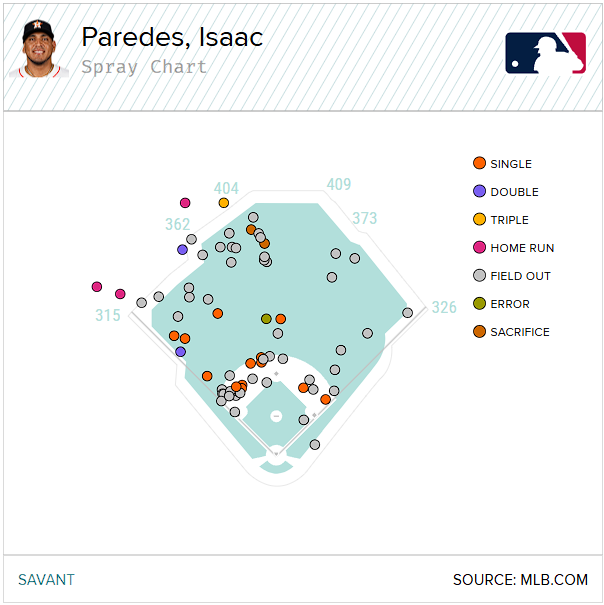

You can think of it like this: Paredes swings slowly because he’s trying to replicate one exact contact point every time. Get the bat way out in front, angled up and to the pull side. This approach comes with plenty of mishits, because it’s quite difficult to time the ball well at that extreme of a hitting position. That’s just part of the trade-off, though. Paredes accepts his fair share of foul balls, infield popups, and shanks because one home run can compensate for those outs.

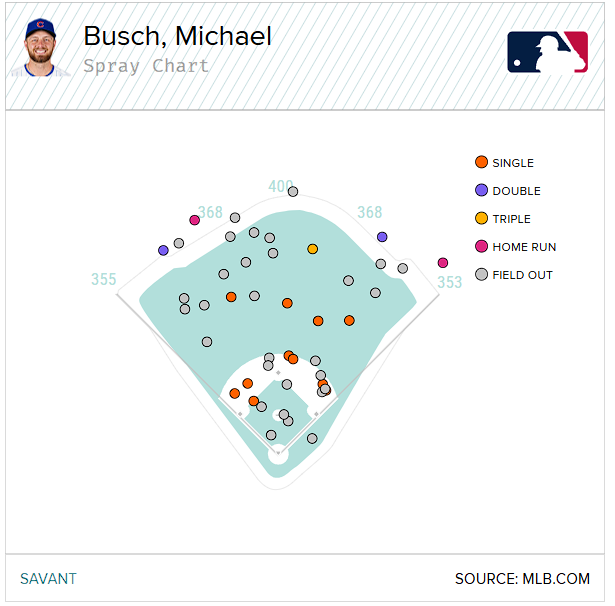

Busch, on the other hand, is trying to square up the ball in the air. He’s not aiming for one part of the stadium in particular. In fact, he’s dead in the middle of the pack when it comes to angle of contact. He’s also short to the ball where Paredes is long, and where Paredes’ batted ball mix is almost comically tilted toward fly balls, Busch is more of a line drive/low fly ball hitter.

The clear benefit of trying to square up the ball instead of pull it is you catch it flush far more often. It’s easier to tag a baseball when you’re happy to go the other way if that’s where you’re pitched. It sounds counterintuitive: If you want to hit the ball hard, shouldn’t you swing hard? But it’s not just about how hard you swing, but also how cleanly you connect with the ball. The truer the collision, the more energy transfers from your bat to the ball. If you square up a 93-mph fastball 95% — in other words, hit it 95% as hard as is theoretically possible given bat and ball speed — with a 70-mph swing, it’ll produce an exit velocity of roughly 100.5 mph. If you instead swing at 78 mph and square it up only 80%, you’ll hit the ball 92.5 mph. Busch is maximizing his opportunities to square up the ball.

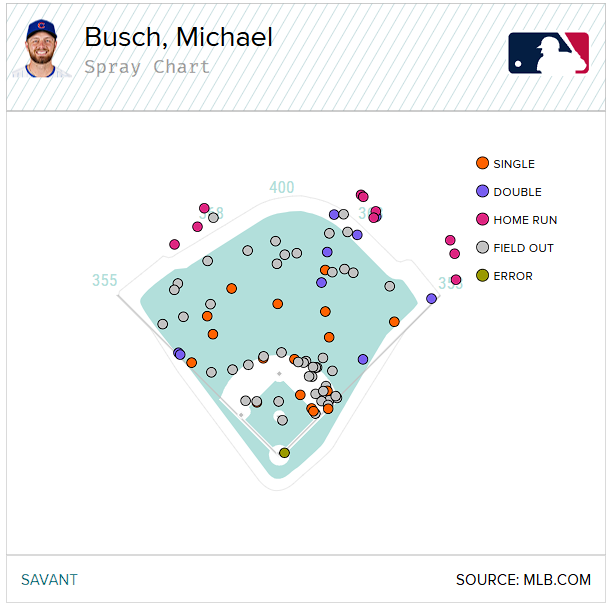

How does he accomplish that trick? By adjusting his swing to the incoming pitch. Here’s Busch’s spray chart when he makes contact with a heater traveling 95 mph or harder:

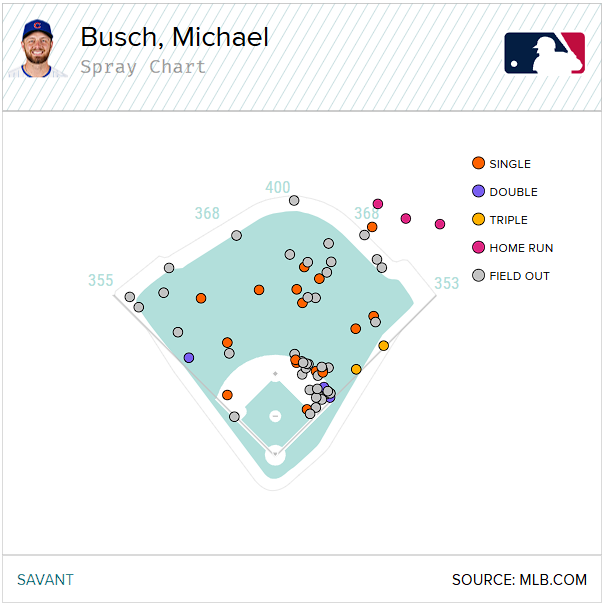

And for comparison, here’s Paredes’ spray chart against the same group of pitches:

If you’re more focused on contacting the ball square than where on the field you’re hitting it, you’ll tend to meet fast pitches deeper and send them the other way, like Busch. Contrast that with his approach against secondary pitches:

His pull rate surges, he sends fewer balls the other way, and he launches a ton of home runs. He does the same with slower fastballs, naturally – if a pitcher gives him a chance to turn on the ball, Busch is happy to oblige him:

It’s a strange but profitable way to hit. No one in all of baseball produces higher exit velocities with slower swings. But there is, in fact, an easy comparison: Busch’s teammate Justin Turner. At his peak, Turner operated the same way; he was never a bat speed god or even a demigod. Instead, he tailored his approach to the way he was pitched and put the ball in the air with a slowish but accurate swing that led to hard aerial contact aplenty.

Turner posted a 136 wRC+ over nearly a decade with the Dodgers using that approach. He hit far more doubles than homers over that time, and that’s also what I expect Busch to do long term, 2025 homer binge notwithstanding. His swing is similar to Turner’s, which brings me to another key part of Turner’s success: avoiding strikeouts.

Busch struck out a lot as a minor leaguer, and he struck out a lot in 2024 — 28.6% of the time to be exact. He isn’t blessed with Turner’s preternatural contact skills, so he’s never going to strike out as rarely as Turner did at his best. For his entire career, Turner has a 71.4% contact rate when he chases pitches outside of the strike zone. Busch’s career mark is 48.3%. They’re much closer when it comes to in-zone contact – 89.3% for Turner, 85.2% for Busch – but that out-of-zone difference is meaningful.

In the end, I think it’s a trade-off that Busch is happy to make. No one hits well on those pitches outside the zone. Even Turner, a master of making out-of-zone contact, hit for a desultory .286 wOBA when he put them in play. By comparison, he put up a .419 wOBA when he hit a pitch within the boundaries of the zone. (These are Turner’s numbers during his time with the Dodgers, when he was at his best.) In other words, Busch’s whiffs come largely on pitches that he wasn’t going to do much with anyway.

Could he change his two-strike approach? Absolutely. He’s missed on 48% of his chases with two strikes in his major league career, a poor mark for someone who has demonstrated solid in-zone bat control. But that adjustment is small potatoes, and this year he’s already cut his strikeout rate by six percentage points because he’s chasing less frequently, all while maintaining his spectacular and spectacularly strange production on contact.

Could we be seeing the start of a career that will end up looking like a left-handed version of Turner? I’m hesitant to predict that outcome, because during his prime years Turner was an outlier, a talent who succeeded like no one else in baseball. But I do feel comfortable saying this: Busch’s success isn’t a fluke. His approach might not line up with what we see from most players these days, but that doesn’t mean his performance isn’t for real. Loud, elevated contact is good. How hard you swing matters, but only if you hit the ball. On that note, I’ll leave you with this: