In 2023, Mets left-hander David Peterson struck out 128 batters in 111 innings. Peterson’s strikeout rate that year, 26.0%, was 27th in the league out of 127 pitchers who threw 100 or more innings. He was tied with Zac Gallen, not far behind Luis Castillo, Gerrit Cole, and Zack Wheeler.

The next year, Peterson’s strikeout rate dropped by more than six points, to 19.8%, but he shaved three-quarters of a run off his FIP, and more than two runs off his ERA. This year, Peterson is striking out 21.5% of opponents, and after Wednesday night’s complete-game shutout of the Nationals, his ERA is 2.49, which is 14th among qualified starters.

But I thought striking batters out was good! How did Peterson turn into this unhittable monster while running a lower strikeout rate than Shane Baz?

Well, the strikeout thing, it turns out, never really suited Peterson all that well. In 2023, he was working outside the strike zone, trying to get batters to chase. He isn’t a hard thrower; his two fastballs mostly work in the 91-93 mph range. The 6-foot-6 Peterson does get a little bit of extra zip — or perceived zip, anyway — thanks to 95th-percentile extension, but he’s not gonna blow hitters away.

Nor was he getting hitters to chase; his O-Swing% in 2023 was 28.8%, bang-on league average.

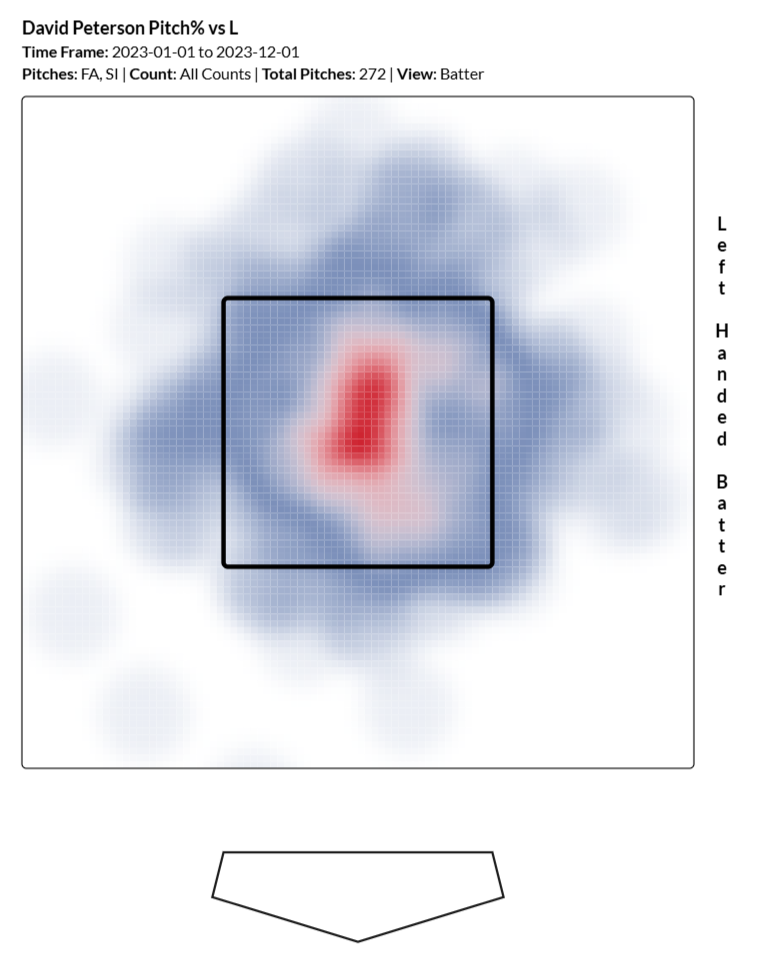

Meanwhile, when Peterson was working within the zone, hitters weren’t getting fooled either. Here’s the heat map from the 2023 for Peterson’s two fastballs (his four-seamer and sinker) to left-handed hitters:

Now, look. I don’t have all the answers, and this is just a theory, so take it for what it’s worth. But I suspect that throwing 91 mph fastballs down the middle is going to lead to a lot of hard contact.

At least, that’s what happened to Peterson in 2023. Lefties hit .264 against his fastballs, with an xBA of .277. They were even more relentless against breaking pitches, against which they hit .319. Overall, Peterson got tagged with an opponent wOBA of .357 (which is exactly Bryce Harper’s wOBA in 2025), and an xwOBACON of .416, which was in the bottom 5% of the league.

A pitcher who allows that quality of contact had better miss a lot of bats, and Peterson didn’t really. His chase and whiff rates were both good, but not great, in 2023. The result: an ERA over 5.00.

Well, dangling the baseball outside the strike zone didn’t work, so let’s try something different:

Zone Time for David Peterson

| Year | Zone% | O-Swing% | Z-Swing% | Contact% | P/BF | P/Out |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 46.0% | 28.8% | 64.6% | 72.7% | 4.00 | 5.91 |

| 2024 | 49.4% | 29.4% | 66.0% | 77.0% | 3.68 | 5.17 |

| 2025 | 50.7% | 31.5% | 62.7% | 77.6% | 3.75 | 5.18 |

Starting in 2024, Peterson began throwing the ball in the zone more. His in-zone rate has jumped about four points for breaking balls, and an incredible 10 percentage points for fastballs, from 2023 to 2025.

The most obvious effect of this new approach is that Peterson’s walk rate dropped from 10.2% in 2023 to 9.0% in 2024, and 7.6% this year. Throw in the zone more, issue fewer walks. That makes sense. He’s also gotten more efficient; each batter faced is costing Peterson a quarter of a pitch less now than it did in 2023. Each out costs three-quarters of a pitch less; two years ago, 100 pitches got Peterson 17 outs. Now that many pitches get him 19.3 outs. That’s the difference between 5 2/3 innings and 6 1/3 innings per start.

What’s slightly less intuitive is that where Peterson was getting lit up on contact in 2023, he’s living with contact much better now. Opponents can still hit the ball hard — his hard-hit rate is 46.3% this year, which is pretty bad out of context and actually up a couple ticks from 2023 — but they’re not doing as much damage.

Peterson has become very good at keeping the ball off the barrel of the bat, and therefore limiting the impact, so to speak, of hard contact. In his shutout victory over Washington, Peterson got just 13 whiffs on 50 swings — a pretty pedestrian total, especially for a start of that quality. He also allowed 13 batted balls with an exit velo of 93 mph or more — just over half the 25 balls put in play against him.

But only one of those 13 screamers came off the bat at a launch angle between 15 and 50 degrees. (That one, an eighth-inning double by Luis García Jr., was Washington’s only extra-base hit of the day.)

Peterson doesn’t miss that many bats, and it’s not especially difficult to hit the ball hard against him. But hard contact isn’t much good when it results in a groundout or a medium-depth fly ball or, at most, a single. It’s hard to build a big inning by stringing together singles.

When I see a pitcher change his output to this extent, especially when he pairs a lower strikeout rate with better overall numbers, I usually expect to see a change in repertoire. A switch from a slider to a sweeper, a reworked changeup, or (tosses a quarter in the swear jar) a new cutter.

Not Peterson. He’s still throwing the same five pitches at the same velocity, with about the same spin rates and movement profiles.

What I will say is that Peterson is throwing his various pitches, and especially his two breaking balls, with much greater consistency.

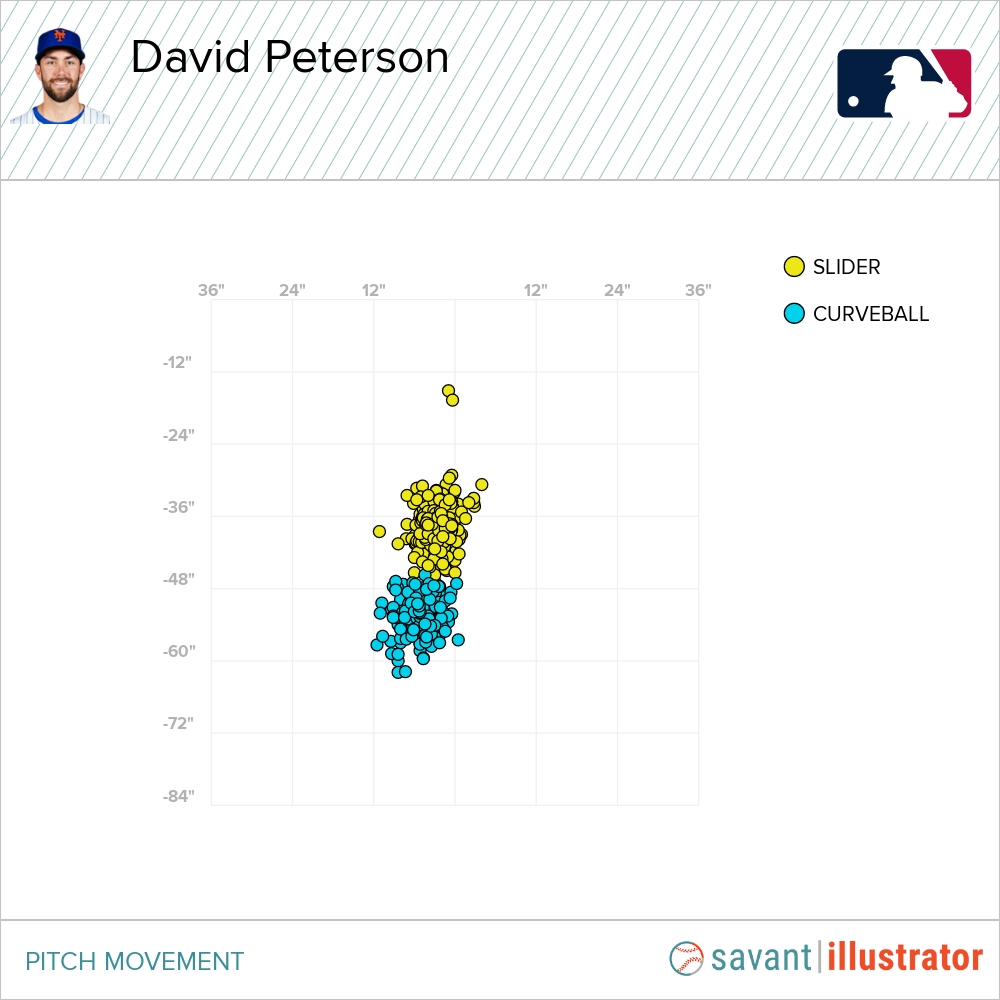

Back when he was trying to bait hitters to chase, Peterson splashed his slider basically anywhere mid-zone and below, and the movement was kind of all over the place. Here’s how Peterson’s two breaking balls moved in 2023:

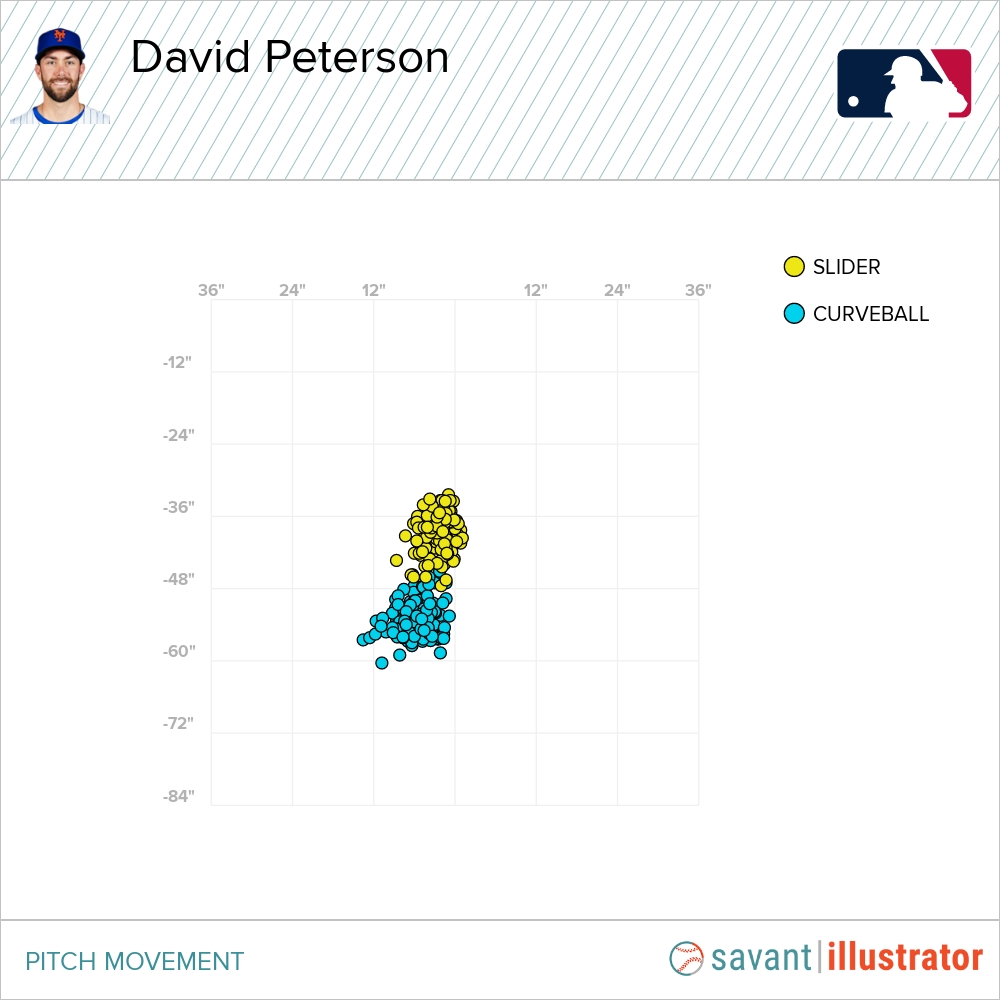

And here they are in 2025:

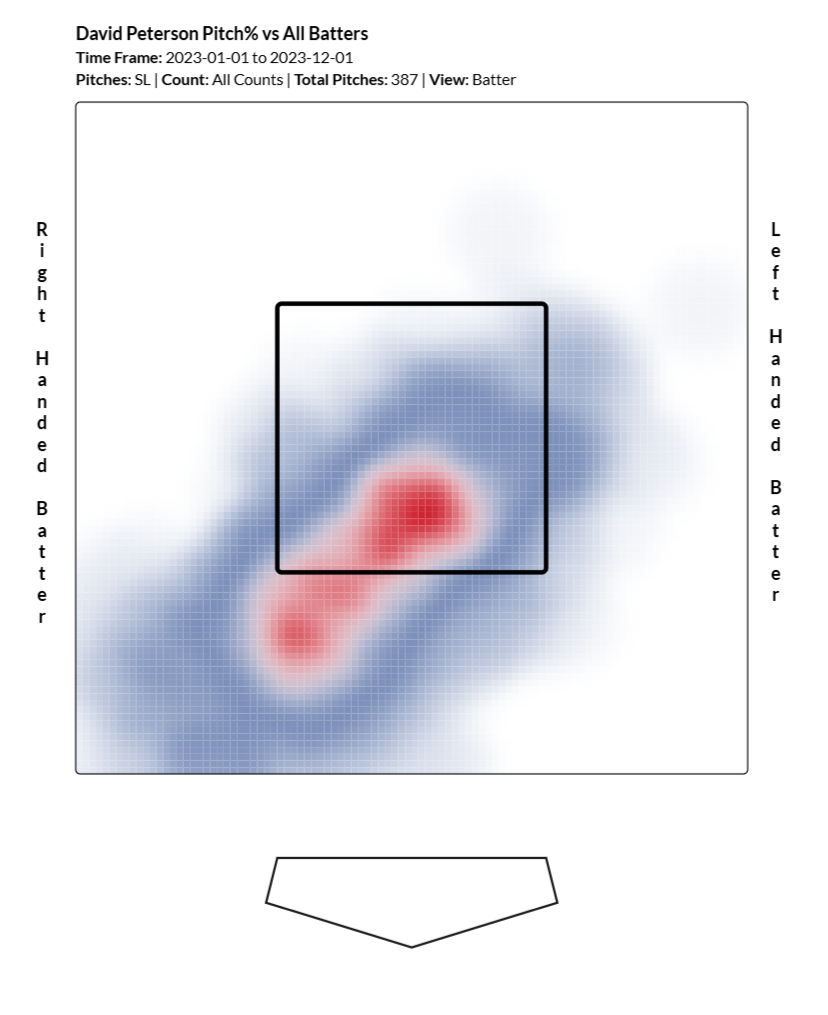

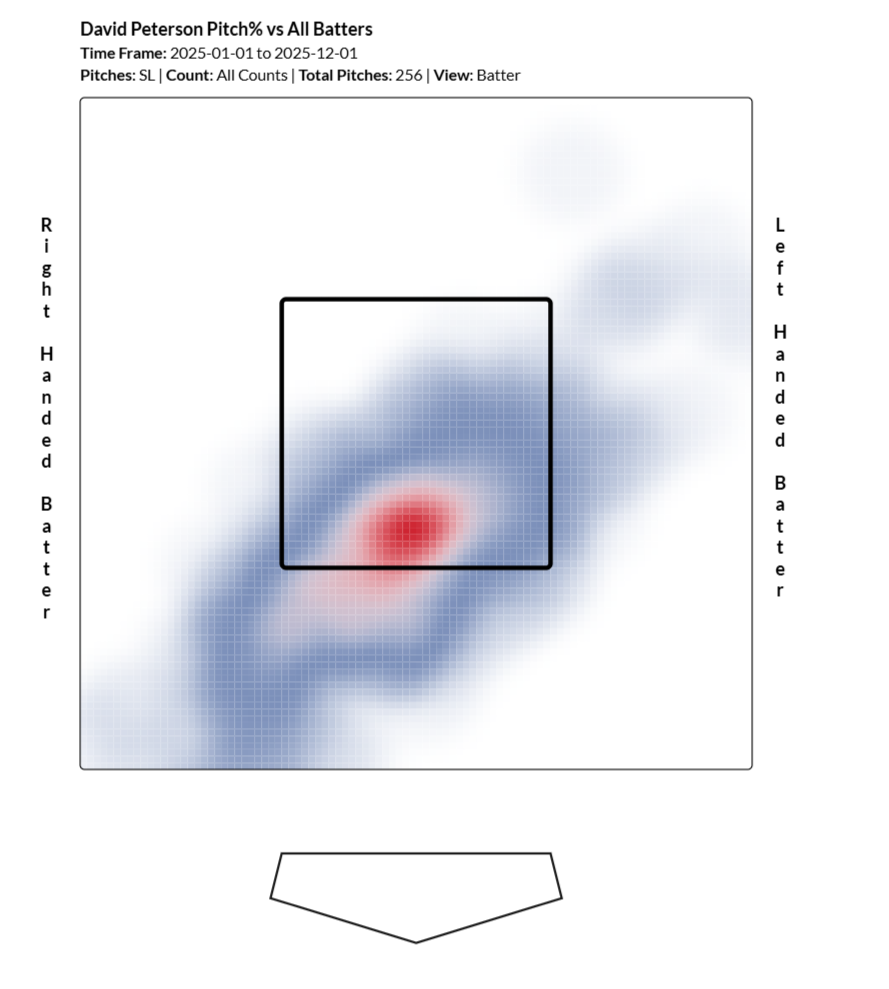

The slider in particular is much more precise. So precise I instinctively want to call it sharper, though it’s not, really. It doesn’t have remarkable movement in either direction. But with more consistent movement, Peterson can be more precise in where he throws it. Here’s where the slider ended up in 2023:

And here’s where he’s throwing it this year:

While opponents tagged Peterson’s slider for a .355 wOBA in 2023, they’re only wOBAing .225 this year. A liability when thrown as a chase pitch, the slider is a major asset now that Peterson’s throwing it for strikes.

See? You don’t have to throw hard or rip off big spin rates after all. You just have to throw strikes.