The looming presence was hard to ignore as I settled down with the smugness that comes from ensuring that your long flight to Australia from Heathrow would be slightly eased by grabbing one of the extra legroom seats in economy. Unfortunately, this piece of good fortune had not gone unnoticed, and that is why the 6ft 6in, 112kg frame of Inspector Paul Ackford of the Met Police, Harlequins, England and now the British and Irish Lions was in my face pleading to swap seats. “Chris, you can’t let me fly 24 hours to Australia in that seat (pointing to one of the packed rows in economy, which is where they put the Lions players). Please swap and you can have as many interviews as you want in Oz.”

Spotting a journalistic opportunity, I agreed, which on reflection was a schoolboy error on a first Lions tour, and as Ackford—who would later join the press pack after retiring—settled into my seat, I made my way a couple of rows back to take his spot alongside a young Dai Young, the Wales prop.

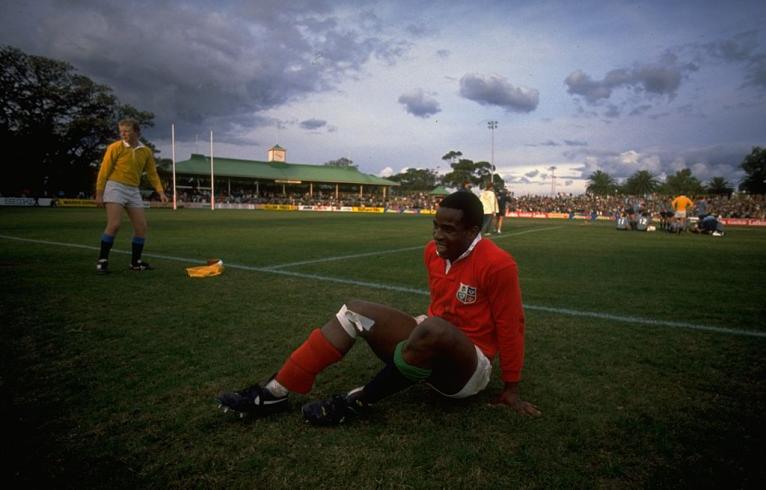

Not too bad, I mistakenly thought, because as the wheels left the Heathrow tarmac, Chris Oti, the England wing immediately in front of me, put his seat back as far as it went and remained in that space-destroying semi-horizontal position until we landed in Oz.

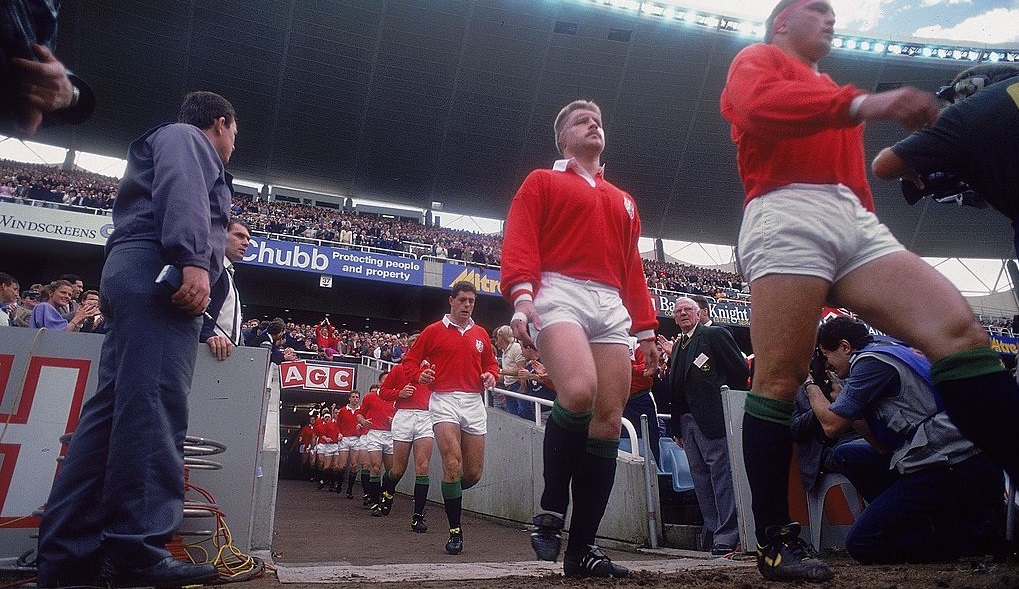

At the start of what would be a tour of incredible highs and some lows—and the kind of access to players the current press pack in Perth following the 2025 edition of the Lions can only dream about—my abiding memory will be seeing the look on Wade Dooley’s face from one of the middle seats in the centre row of economy as he tried to work out how his England second-row partner was in an extra legroom seat. Then again, Ackers was an Inspector and Wade a PC.

Wade would feature strongly as the tour progressed, bringing his unique skills to a Lions pack that would eventually maul the Wallabies into submission in a titanic and highly controversial second Test victory that squared the series.

That was the ninth fixture of a 12-match tour, the first time the Lions had given Australia their full attention, and with the players all amateurs they had to deal with the fact the tour committee had booked them into economy. You could actually watch the Lions players training in 1989—no exclusion zone then—with an early session showing me just how much Brian Moore wanted the Test No. 2 jersey. He was much smaller than Wallaby hooker Tommy Lawton, which made Ireland’s Steve Smith the favourite to play in the Tests. However, right from the start Moore set out his stall, and when captain Finlay Calder and the back rowers did their “extras”, there alongside them was the England hooker, making his point with typical aggression.

While the players adjusted to the time difference at the start of the tour, coming round from yet another jet lag–affected sleep I realised that time was running out to deliver my first tour feature for the News of the World, which I was looking after along with the London Evening Standard. With no massed ranks of press officers or scheduled interview times that are now the norm, I had a dilemma.

Time to call on the experience of my great mate Stephen Jones of The Sunday Times. “I haven’t got anything for the NOW, got any ideas?” Being the ultimate Sunday pro, Steve asked me who I had been sitting next to on the plane, and that was Dai Young. “Did you have much of a chat on the flight?” Through the fog of jet lag I started to piece together the fragmented asides and the tale of how Young had been on holiday in Oz when he was drafted into the Wales Rugby World Cup team that finished third at the inaugural tournament in 1987. That will do.

Access to the 1989 squad was simple—you just asked a player for a chat on a tour that took you to venues like the Apex Oval in Dubbo and Barlow Park in Cairns. Clive Rowlands, the tour manager, was happy to accommodate this relaxed working relationship, which was incredibly helpful given the press pack was large, with representatives from all four Home Nations. The current Lions tour party is made up of 38 players in a total travelling group of more than 90. In 1989 there was Rowlands, coach Ian McGeechan, assistant Roger Uttley, a doctor, and Kevin ‘Smurf’ Murphy, the physio, to look after 32 players.

Rowlands, the former Wales captain and scrum-half, was a passionate speaker and after the first Test defeat, 30–12 in Sydney, he addressed the assembled media. It was classic Rowlands, as he started off his speech—designed to try and blow away some of the gloom—by starting with the warning that “A wounded lion …” He never got to the bit where he added “is a dangerous animal” because his tangent took him all over the English language with a speech that my late colleague Steve Bale, of The Independent, took down in his faultless shorthand. It became one of his party pieces as he recited later in the tour the speech that never got to the punchline.

The 1989 tour was in danger of imploding after that first Test defeat, and as we drove to Canberra for the next game against the ACT there was real concern that the Lions had blown it. That feeling became even stronger as the Lions went 17–0 down to the locals, who couldn’t believe their luck.

At half-time I escaped the portakabin that served as a press box at Seiffert Oval and outside I bumped into legendary Irish rugby writer Ned van Esbeck, who was so annoyed by the mess the Lions had served up he was in danger of chewing off the end of his trademark pipe. However, the half-time team talk that McGeechan delivered turned the tour on its head, with the Lions running out 41–25 winners. The performances of Rob Andrew, Jeremy Guscott, Scott Hastings and Wade Dooley earned them places in the second Test side that ran out for the Battle of Ballymore in Brisbane.

The build-up to the match included a classic Dooley moment when Uttley, the forwards coach, asked each of his pack to talk about their opposite number, and after the front row of David Sole, Brian Moore and Young had pinpointed the strengths and weaknesses of the Aussies they would crash into, it was Dooley’s turn. Uttley asked Dooley what he knew about Wallaby lock Steve Cutler. “He’s a student,” came the reply, and PC Dooley sat back down. Dumbfounded, Uttley asked Dooley to expand his answer and the big man rose to his feet and added, “I hate students.”

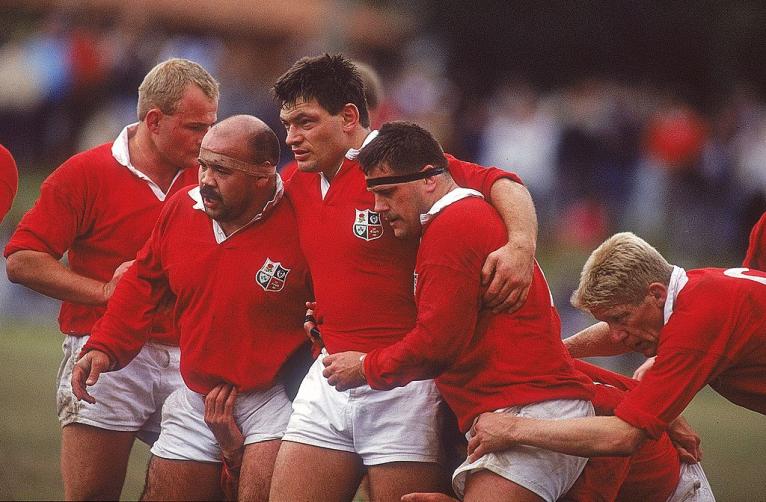

With Mike Teague fit to join the back row, the Lions had found a pack of forwards to do a job on the Wallabies, although the trigger for the big brawl was started by the unlikeliest of pugilists—Wales scrum-half Robert Jones. Coach McGeechan suggested he unsettle Nick Farr-Jones to help the cause, and Jones stood on Farr-Jones’s foot at the scrum. When the Wallaby captain pushed him away, it signalled a pile-in.

With the Wallabies rattled, bloodied and bruised, the Lions won 19–12, with Guscott’s solo try helping settle a contest whose fallout lasted well into the following week. The Australian board compiled a video nasty along with an official complaint, while the Lions reprimanded Young for kicking Cutler.

The players headed to a rainy break in Surfers Paradise while the press headed to the Sanctuary Cove resort, with one journo assigned each day to ring Rowlands to find out the latest on the furore over the violence in the second Test and any injury updates. Now, it is often mistakenly believed that the rugby media at that time spent the majority of their time on tour drinking. Well, in 1989 we had every reason to raise a glass after that second Test, as newspaper desks were now fully tuned into the tour thanks to the fighting, and so we celebrated. The resort had sub-bars linked to various parts of the complex, and one of these was given over to the Lions media group—but after we drank it dry on the first night, this privilege was, for some reason, withdrawn.

The deciding Test would be settled by a mix-up between full-back Greg Martin and the mercurial David Campese, with the dropped ball presenting Ieuan Evans, the current chairman of the Lions, with the all-important score in a 19–18 win. Ieuan recently told me that during the match, no one had noticed that he had picked up a small rabbit and taken it off the pitch. Then again, the party that followed the win clouded many memories.

For Steve Jones, getting a round of drinks in for a celebrating Gavin Hastings in our hotel became a very costly mistake, as he misheard Gav’s request for a round of Bundy and Cokes as Brandy and Coke. Cue a swift turnaround and another tray full—this time of Bundaberg Rum and Coke. The toast that night was to the Lions pack that had taken care of the Wallabies forwards in the last two Tests, with police officers Dean Richards, Dooley and Ackford leading the way and Iron Mike Teague a colossus alongside captain Calder.

As the players and press headed to the plane home and those economy class seats, we could take comfort from the fact the Lions had proved you can come back from a first Test loss and win the series, while Australia showed they could host a tour—and the lessons they learnt underpinned their 1991 Rugby World Cup triumph. And no, I didn’t give up my legroom seat this time.