Last week, we received a mailbag question from a Jacob Young fan named David. Actually, it was a multi-part question, and the third sub-question was particularly fun: Are we now in an era of Peak Centerfield Defense? It seems like every team has a centerfielder that can go get it.

My gut reaction to this question was simple: Yes, we’re probably in an era of peak center field defense. I suspect the game has probably been in that era more often than not ever since integration, and that peak has kept on rising. I saved David’s other sub-questions for this Saturday’s mailbag, but for this particular one, I thought it might be fun to think it through and dig deeper than I could in the mailbag.

First, let me explain my gut reaction. More than any other position, center field rewards pure athleticism, and the athletes keep getting better. The player pool keeps expanding, and players (and humans in general) keep getting bigger, stronger, and faster. All of this means the bar to make it to the majors at all is that much higher. I’ve got baseball-specific reasons, too. The league keeps getting better at positioning defenders where the ball is more likely to go, allowing them to make even more of their superlative talents. And because we keep getting better at accurately measuring defensive contributions, we’re able to recognize and reward defensive value better than ever.

After saying all that, though, I have to admit the obvious: There’s no way to know the answer definitively. We have precious little Statcast data about Ty Cobb’s sprint speed or Duke Snider’s reaction time. Up until this century, play-by-play data is all we have to go on in evaluating defenders. Sean Smith analyzed that data to create a defensive metric called Total Zone, which is what informs the defensive grades on our leaderboards up until 2002, when more advanced defensive metrics like UZR, DRS, and FRV take over. Today’s metrics are nowhere near perfect, but take a moment to stop and think about how far we’ve come. Statcast can tell you exactly how much time every outfielder had to reach every ball, how far they traveled, how fast they ran, how efficient their route was, and how quickly they reacted as the ball came off the bat. That’s a long way from extrapolating from play-by-play data.

I realize that David wasn’t necessarily asking about the overall quality of center field play, but whether we’re living in a time when we’ve got a particularly high number of excellent defenders. It feels that way, right? Think of all the center fielders right now whom you’d classify as extremely good defenders. My list would definitely include Young, Pete Crow-Armstrong, Denzel Clarke, Ceddanne Rafaela, Victor Scott II, and Jose Siri, and I wouldn’t argue with anybody who also included Byron Buxton, Julio Rodríguez, Jake Meyers, Kyle Isbel, Michael Harris II, Daulton Varsho, Harrison Bader, or Myles Straw. I’m not sure what’s happened to Brenton Doyle, but before the season we would have put him on this list, as well. All of a sudden, we’ve got half the teams in baseball with an elite center field defender.

Now maybe it’s always felt that way. Just to pick a date out of a hat, if you go back to 1999, you’ve got defensive standouts like Andruw Jones, Mike Cameron, Carlos Beltrán, Steve Finley, Darren Lewis, and Kenny Lofton. If you go back to the 1950s, you’ve got Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, and Duke Snider all in the same city. For that reason, I decided to see what I could do with the numbers available to me.

Even if we can’t know the answer definitively, we can have some fun with the data at our disposal. We have all these different numbers – TZ, UZR, DRS, DRP, OAA, FRV – but none of them matches up perfectly. They’re all working off different data sources. They’re all using different methods based on different philosophies. They’re looking at different eras with different styles of play. They’re all grading on different curves, judging players according to the league average in their particular year, which makes it very hard to compare players from different eras. It’s a glorious mess, but it means that we need to think of some other ways to analyze things.

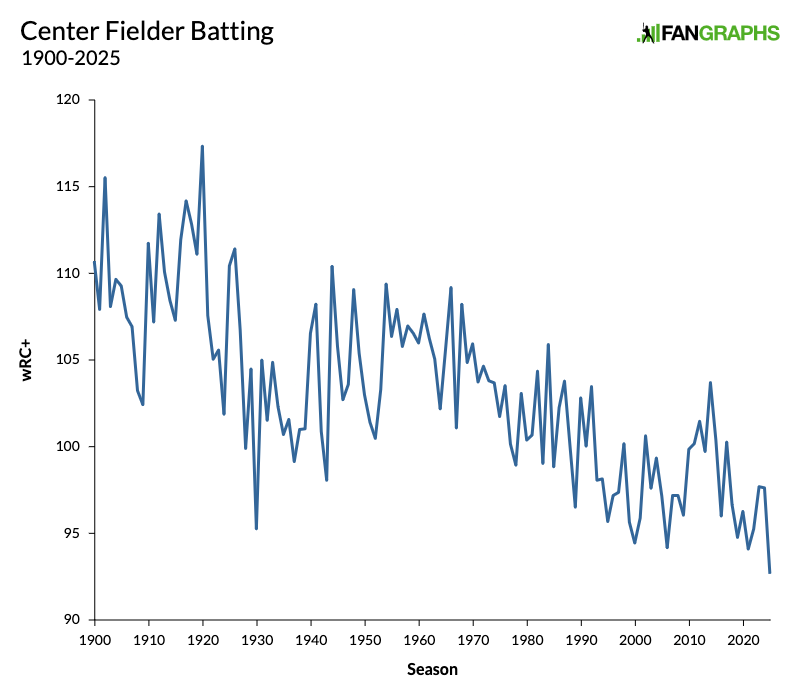

Let’s start by considering how center fielders are earning their playing time. If you’re not hitting well and you’re not fielding well, you’re probably not going to stay on the field. If you’re doing one well, you can get away with doing a worse job at the other. Now take a look at how center fielders have hit since 1900.

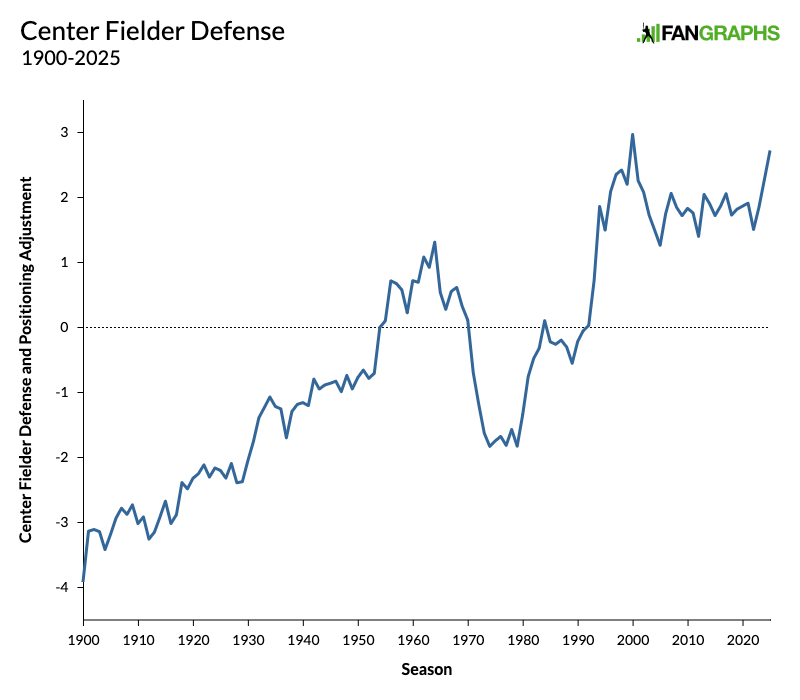

That graph is going nowhere but down, and it’s been on that trajectory since the beginning. This season, the league has a combined wRC+ of 92 at center field. If it holds, it would be the lowest mark ever recorded. However, center fielders aren’t worse players than ever. Here’s a graph that shows defensive run value per 600 plate appearances. This is just the Def column that you see all the way on the right of our main leaderboard. Before you look at it, let me warn you that I’m cheating a little bit by showing it to you.

Here’s how I’m cheating. Not everybody is playing center field all the time. It just shows players whose primary position is listed as center field. We stopped using total zone for these numbers in 2002, so the more recent numbers are based on an entirely different formula. But the overall trend is about as unambiguous as it gets. For the first half of baseball history, the numbers say that center fielders weren’t necessarily great defenders, but that changed in the late 1950s, then cemented itself in the late 1980s.

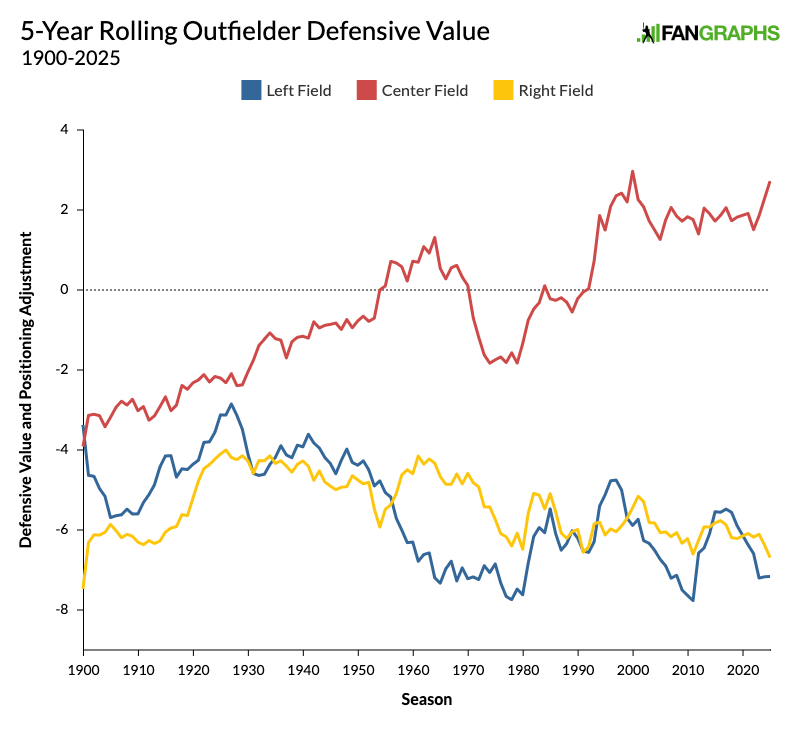

The big reason why this is cheating, though, is because these numbers include a positional adjustment. As you likely know if you’ve made it this far, positional adjustments give more credit to tougher defensive spots and take credit from easier ones. If you look at center field defensive metrics for any one year, they should be right around zero more often than not. However high the bar is, there will be good, average, and bad center fielders, and they’ll cancel each other out. This graph is saying that the bar has gotten higher over time, compared to other positions on the field. That’s all the more apparent if you look at the same graph with the corners included.

This shouldn’t necessarily be my persuasive argument. After all, I didn’t crunch the numbers and decide on the positional adjustments myself. I’m just showing you their effect on the way we value outfielder defense. However, when you view this alongside the decreasing wRC+ of center fielders, the conclusion is obvious. Defense has never been a more important part of the job, and the gap between defense in center field and the corners has never been higher.

Knowing all this, what makes me say that this very moment could be peak center field defense? For starters, players are just plain faster these days – and I don’t just mean faster than they were in the 1950s. We have 11 years of Statcast data tracking every player’s average sprint speed. For each year, I calculated the sprint speed of the average center fielder, prorating it by innings played (and ignoring any player who didn’t play enough to register a sprint speed). In the first three years, from 2015 to 2017, the average center fielder had a sprint speed of 28.4 feet per second. In the last three years, from 2023 to 2025, the average is 28.6. That may seem like a small change, but it’s also taking place over an awfully short timeframe. We can honestly say that center fielders are measurably faster today than they were just 10 years ago! It’s not hard to extrapolate further back in time.

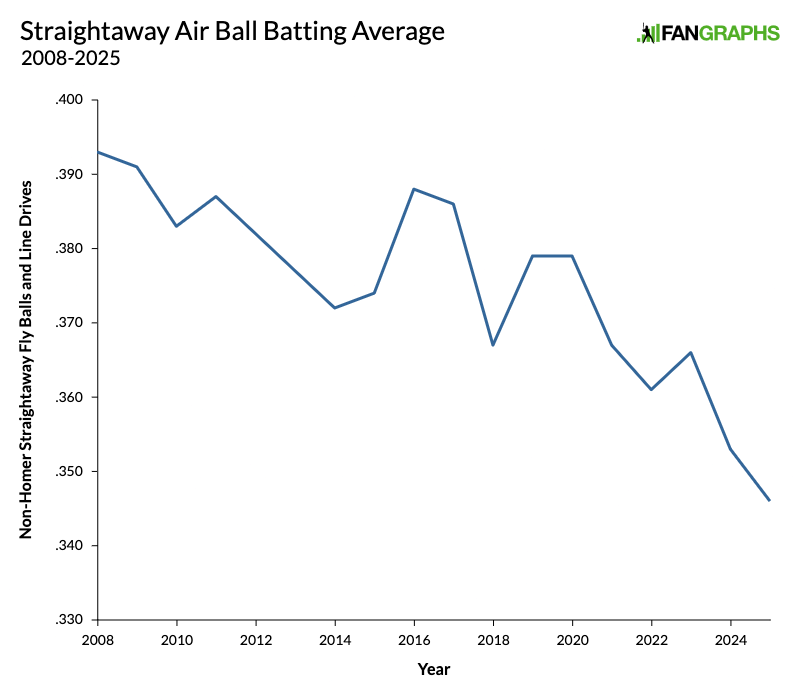

If we extend our gaze a bit to take in the entirety of the pitch-tracking era, we can see that balls just aren’t falling in the way they used to. The graph below goes back to 2008, and it shows the batting average for every ball classified as either a line drive or a fly ball hit straightaway (not including home runs). It starts at .393 and ends at .346. Nearly 50 points of average just disappeared into the gloves of center fielders.

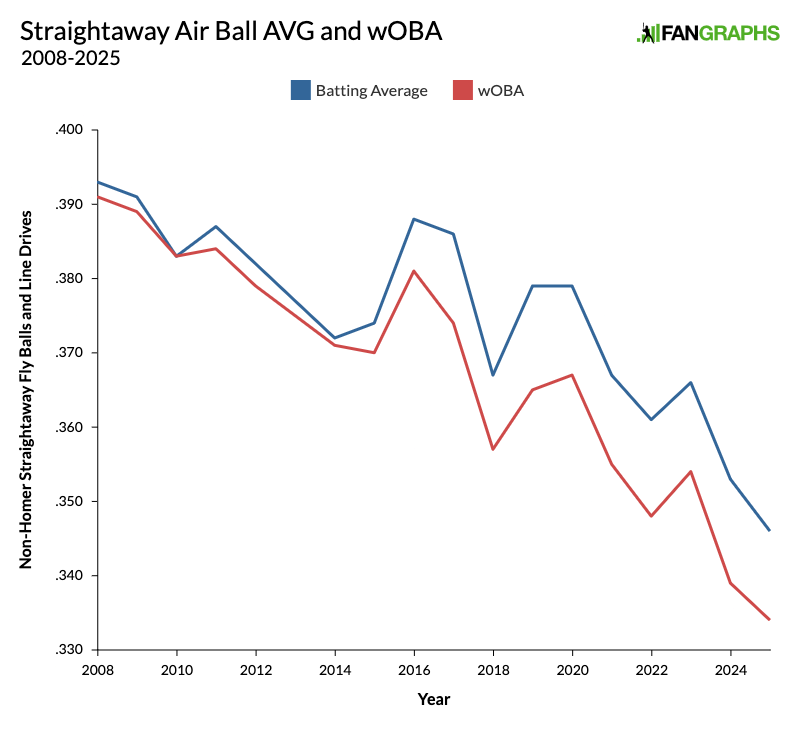

This is pretty stark, but even this graph is underselling the difference a bit. Here’s the same graph, but now it includes wOBA, too. The new red wOBA line falls even steeper than the blue line. Center fielders aren’t just robbing batters of more hits. They’re also better at holding batters to singles and preventing extra-base hits. That drop-off is nearly 60 points.

I think this is about as definitive as it gets. Since 2008, there’s never been a worse time to hit the ball to center field. So far as we can tell, defense has never been a more important part of a center fielder’s job, and center fielders have never been so much better than corner outfielders. In all, we’re probably at peak center field defense right now. And we’ll probably stay there.