On Tuesday night, Ranger Suárez aced his toughest test of the season. Taking on a red-hot Astros team (they’ve posted a 135 wRC+ over the last 14 days) that demolishes lefties (they’re first in wRC+ vs. left-handed pitchers), Suárez hardly broke a sweat. He tossed 7.1 scoreless innings, allowing just three hits, before Cooper Hummel parked his 99th pitch of the game into the right field seats.

The start may have ended on a sour note, but Tuesday’s performance was the cherry on top of an unbelievably sweet run for the 29-year-old southpaw. In his last nine starts, Suárez has allowed eight earned runs. That’s good for a 1.17 ERA over nearly a third of an entire season.

But for some reason, I’m never quite ready to believe. Maybe it’s because his primary fastball sits below 91 mph, or the absence of gaudy strikeout rates, or the lack of a single pitch that grades out as even average by Stuff+ or PitchingBot. Mostly, I think it’s because I perceive Suárez as a fundamentally streaky pitcher. He’s certainly on a run at the moment, and he’s gone on these runs before. During his breakout 2021 campaign, he compiled a 1.24 ERA in his final eight starts of the season. And there were the first three months of 2024: a 1.85 ERA over a 99 inning span.

I’ve written these stretches off as part of the deal with a pitcher who relies so heavily on his excellent command. When it’s dialed in, Suárez is untouchable. When it’s off a tad, he can look suspiciously replacement-level. But after this latest stretch, I’ve started to wonder if the “streaky pitcher” framing sells Suàrez short. Over a significant sample, he’s pitching like one of the 20 or so best pitchers in the sport. Is he more than just a guy who mixes hot streaks with mediocre performance?

The question is more than just academic. This is Suàrez’s final season before free agency. Between Dylan Cease and Framber Valdez, there are two starting pitchers clearly at the top of this winter’s market. But if Suárez can keep this up, he may be the best of the rest. Would it surprise you to hear that, since the start of 2024, Suárez ranks 16th in pitcher WAR, ahead of Logan Gilbert, Michael King, and Hunter Greene?

It certainly surprised me. But handing out a nine-figure contract to Suárez requires a belief in skills that are less undeniable (more deniable?) than, say, Cease’s heater or Framber’s power sinker. From a shape perspective, Suárez’s primary pitch is pretty similar to that Framber sinker, but perhaps without the power modifier — Suárez’s sinker moves 3.5 mph slower on average. Clearly, Suárez isn’t relying on velocity. So how does he do it?

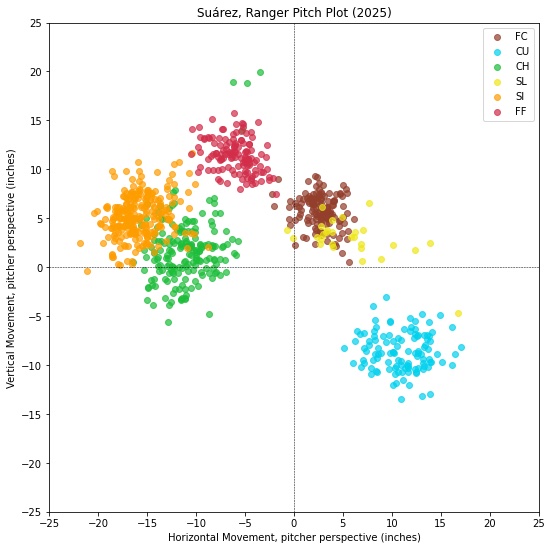

In short: He induces weak contact by wielding a deep mix with pinpoint command:

Between Nick Martinez, Spencer Schwellenbach, and Max Fried, these sorts of pitchers have been a fascination of mine. But Suárez is also a bit different. Unlike Schwellenbach and Fried, Suárez is working with below-average velocity. And unlike Martinez, he lacks a carry fastball to throw at the top of the zone. To succeed, he must work the outer edges and the shadow zone below the knees. At the moment, he’s walking that tightrope with precision.

The bedrock of Suàrez’s approach is the interplay of his sinker and cutter. Because he tortures lefty hitters, opponents tend to stack their lineups with righties, as the Astros did on Tuesday — he’s only faced 31 left-handed hitters the entire season.

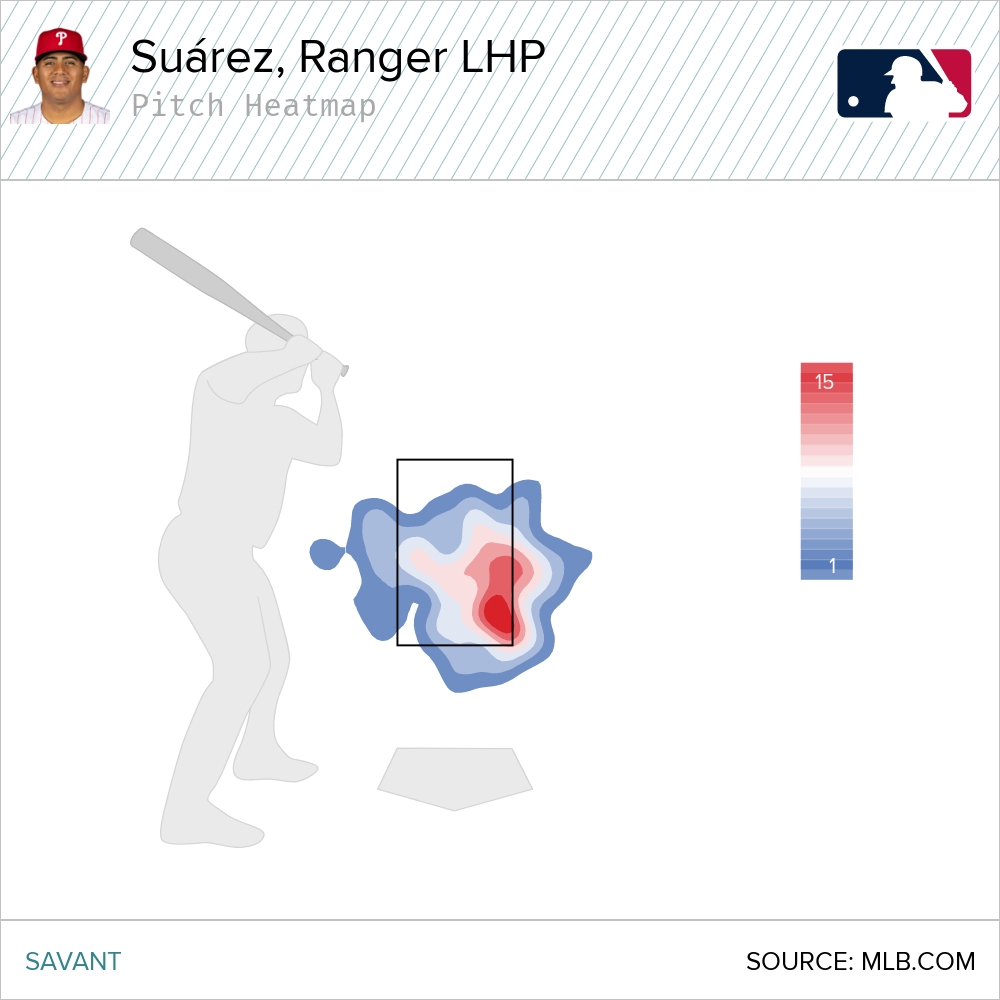

Opposite-handed sinkers are generally considered suboptimal, but Suárez is staying off barrels with that pitch while racking up a ton of called strikes. That owes to his primary target being on the outer edge; he concentrates a plurality of his sinkers on the low-outside corner, far from where anyone could conceivably punish the pitch:

Primed with the expectation of these wide sinkers, Suárez busts the cutter inside with extreme effectiveness. These pitches tunnel very effectively together, traveling along the same trajectory before splitting off in separate directions. When Suárez manages to get the pitch in on the hands of a right-handed hitter, they’re essentially helpless — among pitchers with at least 100 cutters thrown this season, Suárez ranks first overall in exit velocity allowed. It’s a weak contact machine:

These two pitches allow Suárez to get ahead in early counts and generate weak contact when he falls behind. But when he gains an edge, he pivots to his two out pitches.

The curveball is eye-catching, drooping into the strike zone at 74 mph with two-plane movement. There’s nothing else in Suárez’s profile that moves remotely like this, and it can catch hitters off guard, though the pitch hasn’t been quite as successful this season as it’s been in past years. Even with questionable effectiveness in a vacuum, the pitch enhances his overall arsenal. (More on this later.) The curveball moves 17 mph slower and drops 14 inches more than the sinker, making it trickier for hitters to lock in on a particular movement pattern.

But it’s the changeup that has emerged as Suárez’s best pitch. He’s throwing it more than ever this season, and the increase in usage has coincided with a subtle shape change. As recently as three years ago, Suárez’s changeup moved exactly like his sinker, with a seven tick gap between the two pitches. These days, the velo differential is more like 10 mph, and the pitch is now cutting relative to the sinker.

This sort of sinker-changeup movement relationship is pretty uncommon. I looked at every pitcher with at least 100 sinkers and 100 changeups thrown, and noted the gap between the horizontal movement of each pitch. Suárez gets nearly five inches of “cut” relative to his sinker, fourth-most among all pitchers in baseball. A couple of those are kick changes, thrown with significant depth relative to the sinker. Suárez’s changeup, by comparison, gets the same amount of drop as the sinker:

Changeup Cut

SOURCE: Baseball Savant

Minimum 100 sinkers and changeups thrown. Changeup cut = sinker horizontal break – changeup horizontal break.

The result? Some really ugly swings. Nobody is squaring this pitch up. Hitters are whiffing 35.9% of the time and managing just a .245 xwOBA on contact.

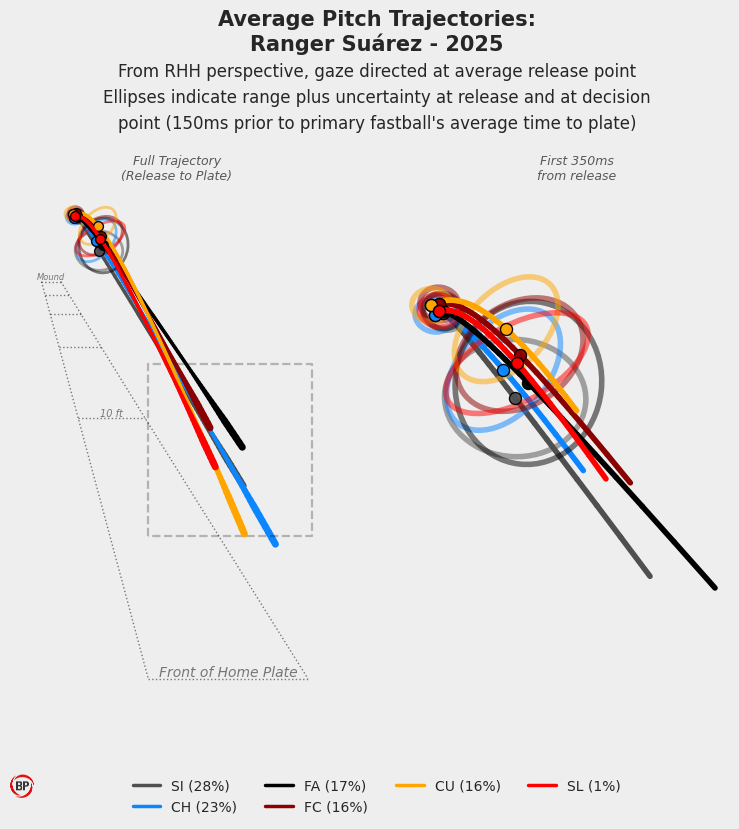

Like Martinez, Schwellenbach, and Fried, Suárez is more than the sum of his parts. All of these pitches in tandem — the four aforementioned offerings, plus an occasional four-seamer — produce an absolutely chaotic look for hitters, as this plot from Stephen Sutton-Brown of Baseball Prospectus shows:

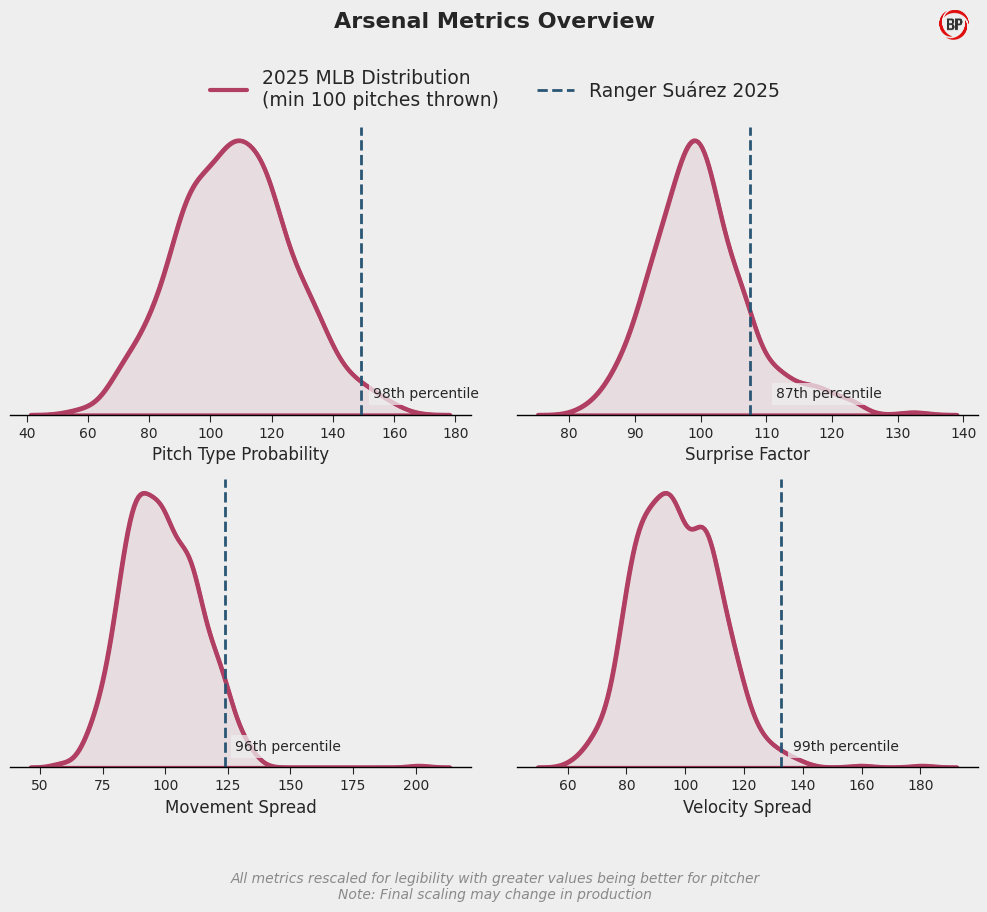

Because Suárez throws so many pitches moving on similar trajectories with roughly equal frequency, hitters have no choice but to guess. As the plot below shows, Suárez ranks as one of the best tunnelers in the league by Stephen’s arsenal metrics:

He ties it all together with pinpoint command. Perhaps that’s clear from the location plots, but the models are here to support that narrative. Suárez’s Location+ numbers this season are off the charts, ranking second among all pitchers with at least 50 innings pitched. BotCMD concurs, giving him a 61 command grade on the 20-80 scale.

It may only matter on the margins, but Suárez also fields his position with more panache than any pitcher, save for maybe Brusdar Graterol. Look at how casually he scoops up this Agustín Ramírez grounder even after initially booting it:

He’s never worried!

The Phillies booth could only laugh after this one:

If you could lock in Suárez’s performance from the last year and a half — a 3.05 ERA and 3.21 FIP — over the length of his next four seasons, he’d easily merit a nine-figure free agent deal. Will teams have enough faith in this deep mix/command profile to make that big bet? It’s a scary proposition. I felt pretty confident Nick Martinez could repeat his 2024 performance but, so far, it hasn’t been pretty. Martinez is running a 4.40 FIP. What’s to stop Suárez’s performance from backing up like Martinez’s did? And what happens if his sinker velo dips from 91 mph to 90 mph, or even 89 mph?

It’s hard to say. But when Suárez is one of these runs, it’s hard not to get swept up in what could be.