Four large Afrikaans men are sat high in the stands of Ellis Park Stadium in Johannesburg. They tick just about every box on the caricature checklist. Thigh-hugging khaki shorts. Thick forearms. Leather veldskoen. They’ve even smuggled in brandy which they’ve injected straight into the flesh of oranges.

They’re there to witness history. In less than half an hour the South African Springboks will take on the New Zealand All Blacks in the 1995 Rugby World Cup final. Their team, representing a country that has somehow held back the horrors of a civil war, will begin as underdogs. But they have a secret weapon. Something already dubbed ‘Madiba Magic’.

“That’s my president, that’s my president” one the burly men repeats through tears as Nelson Mandela makes his way onto the pitch to a sea of cheer and multi-coloured flags. South Africa’s first democratically elected president is wearing a Springboks jersey, once a symbol of apartheid now repurposed as a beacon of unity. In the 30 years since, that green cloth represents the best of a nation still coming to terms with its history.

This scene was shared with John Carlin, author of ‘Playing the Enemy; Nelson Mandela and the Game that made a Nation’. Published in 2008 and later adapted into the 2009 Hollywood blockbuster ‘Invictus’ starring Matt Damon and Morgan Freeman, Carlin’s account remains the seminal telling of the Springboks’ triumph helped heal a fractured land.

“It was the first time in the whole history of South Africa that black and white people joined in a common goal, a common objective,” Carlin says. “My friend who was in the stadium was sitting behind those Afrikaans men and he told me that they, along with everyone else, were overcome with emotion. That’s the significance of it. It was an amazingly uniting moment in what had previously been the most divided nation on earth.”

Three decades have passed. So has Mandela, who died on 5 December 2013. Some social critics have argued that his dream of a ‘Rainbow Nation’ went with him. One thing has endured and that is the dominance of the Springboks. As Rassie Erasmus once quipped without any hint of irony, “We’re the only thing that works in the country”. Another World Cup win in 2007, along with back-to-back triumphs in 2019 and 2023, have cemented the men’s national rugby team as arguably South Africa’s most successful cultural export.

Carlin was witness to one of the darkest chapters in South Africa’s history, presenting a 1993 BBC documentary on political violence. This was a period of great change.

But there is a danger in tethering the success of a sports team to national identity. Trophies don’t feed the hungry or shelter the homeless. They do not compel corrupt politicians to refrain from stealing. They do not alleviate the threat of hijackings and muggings.

As Carlin says, “If you’re going to [believe] that because South Africa are world champions then the country is capable of anything, that we’re going to fuse together and create a wonderful, prosperous and egalitarian nation, then you’re setting the bar far too high.”

He would know. As Carlin The Independent’s South Africa bureau chief from 1989 to 1995, Carlin was witness to one of the darkest chapters in South Africa’s history, presenting a 1993 BBC documentary on political violence. This was a period of great change. The apartheid regime was in its death throes. Revolutionary forces were at war with each other. The fragile hope for a peaceful transition of power was rapidly fading. Amid the chaos, Mandela emerged.

“South Africa was just unbelievably fortunate that at that absolute fulcrum point in its history, Mandela came along,” says Carlin, who spent time with the former president and observed him at public rallies. “The World Cup final was a happy consummation of the whole Mandela project.

“But it was the cherry on the cake. He’d been working on that cake from the day he left prison on 11th February 1990. He was already trying to build bridges and reach out and understand what the enemy was thinking.

“He did an amazing political job of persuasion, of bringing the country together. All the ingredients were there for some sort of hideous endless conflict. It could have ended up like Syria has been for the past 20 years. The ingredients were there. You had political prisoners, you had people who were tortured. There were bitter divisions and racial divides. I think it’s overwhelmingly thanks to Mandela that it didn’t happen. And then that rugby game came along.”

Their [South Africa’s] win has become an indelible milestone in the broader narrative of the new South Africa. And though it has been studied and scrutinised, it is important that it is also viewed as an explosion of joy beyond any greater meaning it may hold.

Would we remember this story if Joel Stransky hadn’t landed a late drop-goal to clinch the title? Would we still regard the 1995 World Cup as a “beacon”, as Carlin puts it, if Jonah Lomu had gone on the tear and knocked the stuffing out of the Boks?

“That Mandela had already turned over so many white people, including the Springboks themselves, suggests that a different result wouldn’t have shifted the narrative too much,” Carlin explains. “South Africans screamed for joy and celebrated together because of Mandela. I believe they would have been disappointed as one if the team lost. The emotional output would have been different, but the sense of togetherness would have remained, I think.”

As it happened, their win has become an indelible milestone in the broader narrative of the new South Africa. And though it has been studied and scrutinised (thanks in no small part to Carlin’s own work), it is important that it is also viewed as an explosion of joy beyond any greater meaning it may hold.

“Life is full of potholes and disappointments, especially in South Africa,” Carlin says. “When moments of joy come along, my God, can’t we simply squeeze every ounce of joy and celebration out of it?”

There has been much to celebrate since. Siya Kolisi’s story has added a new chapter to this sweeping tale. “If Mandela were alive he would have found it fantastic,” Carlin says of a dominant team, captained by a black man and representing “all the shades of South Africa’s demographics”.

The World Cup win has all the classic tropes of a fairytale. The return of a king from exile and imprisonment. Enemies becoming brothers. A people given hope when there was nothing but misery.

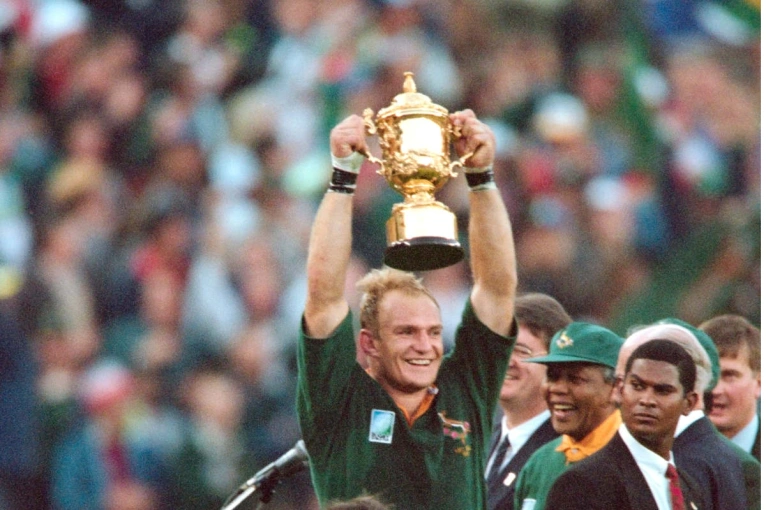

As many as 19 members of the Springboks squad for the July internationals weren’t born when Mandela handed the Webb Ellis Cup to Francois Pienaar and thanked him for what he’d done for the country. But every one of them carry the great man’s legacy. This is more than history now. It is one of the founding myths of South Africa.

It has all the classic tropes of a fairytale. The return of a king from exile and imprisonment. Enemies becoming brothers. A people given hope when there was nothing but misery. This is a parable of forgiveness, of inherited pain turned into power. The victory in 1995 might not have changed South Africa, but it changed the way we see ourselves as South Africans. And maybe that’s what myths are for: not to escape reality, but to teach us how to live with it.