By quantifying these biomechanical metrics in such a manner, we can properly determine the degree to which these tradeoffs can be and should be made, but we can also — more broadly — set a precise and better-informed course of action for each individual athlete based on their needs.

It is, in all honesty, quite rare that an athlete — especially a young athlete — would walk through the doors at Driveline and immediately begin directly training mechanics or velocity because these are upper-echelon sections of training in the hierarchy, and thus rely on a multitude of other more important and arguably more trainable variables to be properly executed. This is, generally speaking, the purpose of the hierarchy however — to organize, structure, and effectively sequence the steps of training necessary to each individual athlete. While some athletes may become frustrated with the lack of direct training and stimulus in their every day training, it is important to outline the means by which they can progress up the hierarchy, and to outline the expectations of what is required to do so. Additionally, combatting the monotony of training during these foundational phases can be accomplished via tools like Pulse, Smart Reports, the Arm Care app, and other technological training tools which create infrastructure and organization to facilitate the athlete’s engagement with their training. If a trainer can engage an athlete with monotonous training on a daily basis, that athlete will then later possess the necessary foundation to execute and benefit from more workload-intensive training phases in a safe manner, thus further underscoring the necessity of such a hierarchy.

These tools, ideologies, and methods of training are all great in theory — but in practice, what is their purpose? Many paragraphs ago now, you may approximately recall a discussion of improving performance at a level that is optimized for an athlete’s injury risk — therein lies our purpose in taking such an extensive and strenuous series of steps; our objective is to improve the performance of an athlete while mitigating their risk of injury. To better outline what such a balance looks like in theory, we can utilize the economic concept of the expected utility. With this concept, we can account for variables like pitching velocity gained, strength gained, the intrinsic risk of injury, the decision-based risk of injury, and additional general training costs (time, money, other allocatable resources), and summarize them to outline the manner in which the execution of the aforementioned steps in training may affect an athlete’s probable gains or losses.

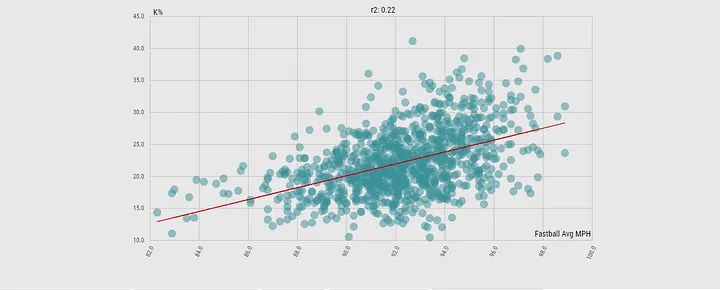

Using this framework, we can model the expected utility of a general athlete as follows: